First published in Accelerate America Magazine March 2015

Those who look to natural refrigerants as the ultimate solution to the cycle of never-ending refrigerant phaseouts have been discussing for several years the hurdles that need to be overcome to accelerate their adoption in the U.S.

Above all, the biggest hurdle is cost. As is usual with technology that has recently come on the scene in the U.S., the cost of natural refrigerant equipment is higher than that of typical HFC equipment.

This is to be expected. The commercial refrigeration industry has had decades to fine tune conventional equipment and drive out inefficiencies. Competition among conventional equipment manufacturers who sell very similar products has kept prices low, and these manufacturers have been able to take advantage of the economies of scale that come with large sales volumes.

Eventually natural refrigerant equipment will get to that point also. In the meantime, the industry is in a catch-22: few are willing to purchase equipment that uses naturals until the price comes down, but manufacturers cannot bring the price down until more people purchase this equipment.

Greater demand in the U.S. would spark a virtuous cycle of events. For example, many of the components for natural equipment are now imported from Europe or Japan, but with increased demand in the U.S., component manufacturers could set up operations here. More customers would also encourage more manufacturers to enter the market, and these companies would compete with each other for business and look for ways to reduce prices.

Other hurdles to natural refrigerants would also be solved with greater volume, including the need for technician training, the lack of real data from stores that allow for equipment improvements, and the shortage of longer-term data on installation and maintenance costs.

If there were enough work on natural refrigerant systems for large numbers of technicians, service companies would invest in training, because they would get a return on their investment. And with greater experience with natural refrigerants across a broader base of end users, supermarkets would share data with each other and work with manufacturers to further improve products. The very fact of more units in use would generate robust data on all facets of the lifecycle cost equation.

So how can we spike demand for natural systems and thereby solve our catch-22?

HELP FROM UTILITIES

An attempt to answer this question took place on January 8th at an industry workshop in Berkeley, California. Sponsored by Hillphoenix, Emerson Climate Technologies and AHT Cooling Systems USA, the meeting brought together supermarket refrigeration executives, utility representatives, equipment manufacturers, and others to discuss ways to boost demand for equipment that uses natural refrigerants and saves energy.

Though the improved energy efficiency of natural refrigerant systems may not be the only — or even the main — reason supermarkets choose these refrigerants, the fact is that most natural

refrigerant equipment brings significant energy savings vs. conventional equipment, which makes them of interest to utilities. Bringing utilities into the equation is a “key stepping stone in the investment and hard work that is going to be required to make natural refrigerants mainstream,” according to Mitch Knapke, Director at Emerson Climate Technologies, one of the sponsors of the workshop.

The day-long workshop tried to “surface some good ideas of how and where to get traction with utility incentive programs,” said Harrison Horning, director of equipment purchasing, maintenance and energy, for Delhaize America.

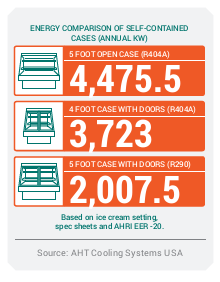

The most obvious opportunity for utility incentives lies with hydrocarbon self-contained units, which can cost about 20% more than their HFC counterparts. Data from AHT Cooling Systems USA (see chart on page 11) show energy efficiency gains of more than 45% for their new hydrocarbon cases vs. their own new HFC cases. (Incentives for self-contained units using carbon dioxide will be considered in a future article.)

Based on those numbers, an average supermarket with 12 self-contained hydrocarbon units saves about 20,000 kWh annually per store. Multiplying the 20,000 kWh per store by the 37,459 supermarkets in the US (according to the Food Marketing Institute) results in a rough, back-of-the-napkin potential savings for supermarkets of 771,130,974 kWh per year. In fact, the savings would likely be higher than that, because the older HFC units that would be switched out likely use more energy than a new HFC unit. Of course, this quick analysis assumes that all 12 cases in an average store are 4-5 foot self-contained spot cases.

Taking the analysis one step further, if the average kWh price for electricity is a flat ten cents, U.S. supermarkets would save over $77,000,000 per year in electricity costs. That sounds like a lot. And it is, though in total our nation’s supermarkets spend about $8-$10 billion per year on electricity.

The premise at the start of the workshop was that prescriptive incentives for new self-contained hydrocarbon units are as close to a no-brainer as you can get in supermarket refrigeration. It should be as easy as comparing the annual electricity usage of a new hydrocarbon unit with the annual electricity usage of the same new unit that uses an HFC refrigerant. In other words, the hydrocarbon unit is compared to what the supermarket would have bought if the hydrocarbon unit did not exist. Just as with a washing machine or a home refrigerator, the annual energy use of self-contained refrigeration units is tested and listed in the equipment’s spec sheets. If utilities don’t trust manufacturers’ energy usage data, wouldn’t it be as easy as plugging both units into the wall next to each other in an independent lab to measure their energy consumption?

If those numbers still aren’t good enough, there will soon be another source: the Department of Energy. By January 1, 2016, all manufacturers of self-contained commercial refrigeration units must measure, certify, and file with the DoE the daily energy consumption in kilowatt-hours per day of each model they sell. The DoE mandates that manufacturers use the “uniform test method for the measurement of energy consumption of commercial refrigerators, freezers, and refrigerator-freezers.” Utilities can easily use those numbers as the basis for their incentive calculations.

Replacing old self-contained units with new ones is slightly more complex. Does one measure the actual electricity usage of the existing unit first and use that consumption number as the basis for the prescriptive incentive? What about the ancient HFC unit that everyone admits shouldn’t even be used anymore? Is it fair or desirable to use that as a baseline for an incentive? Or does one just assume that every existing HFC unit in stores uses an average amount of electricity and base the incentive on that? Or for simplicity’s sake, how about taking the energy usage of a new HFC unit as the baseline, regardless of how much electricity the old HFC unit consumes?

GETTING STARTED

Utilities, supermarkets, and equipment manufacturers could spend a very long time evaluating all of those options to  determine the perfect methodology. Or they could decide to not let the perfect interfere with the good and pick the most conservative option for utilities and go with that. Supermarkets might not receive as much of an incentive as they would with one of the other options, but at least they’d get more than they are currently receiving – nothing. And they’d start getting something a lot sooner than if utilities spend a very long time figuring out the perfect solution to all of these questions.

determine the perfect methodology. Or they could decide to not let the perfect interfere with the good and pick the most conservative option for utilities and go with that. Supermarkets might not receive as much of an incentive as they would with one of the other options, but at least they’d get more than they are currently receiving – nothing. And they’d start getting something a lot sooner than if utilities spend a very long time figuring out the perfect solution to all of these questions.

Derek Gosselin, product manager for systems at Hillphoenix, perhaps stated it best when he said, “The most important thing is to just get started.”

As with other utility incentives, the role of this incentive is to stimulate sales of new energy-efficient equipment while it is still more expensive, allowing manufacturers to achieve the economies of scale that come with larger volumes. Once the market demand is high enough to justify manufacturing components and cases in the US, the cost of hydrocarbon self-contained units will automatically come down. And once the price comes down to levels that are comparable to those of conventional self-contained cases, utility incentives won’t be necessary anymore.

The ideas discussed in the workshop are already bearing fruit, with innovative utility companies in California hoping to have a prescriptive rebates program in place by mid-summer 2015 for hydrocarbon self-contained units, according to Howell Feig, sales director for AHT Cooling Systems USA.

“The opportunity for prescriptive incentives/ rebates for natural refrigerant solutions is in the very near future,” noted Leigha Joyal, energy analyst at Hillphoenix.