First published in Accelerate America Magazine April 2015

On January 8th of this year in Berkeley, CA, Hillphoenix, Emerson Climate Technologies, and AHT Cooling Systems USA brought together supermarket refrigeration executives and representatives from the nation’s major utilities to discuss ways that utilities could help boost demand for energy-efficient natural refrigerant equipment.

After discussing energy incentives for self-contained refrigeration units that employ hydrocarbons (see Part 1 of this article, in the March issue of Accelerate America), the group turned its focus to incentives for supermarket refrigeration systems that use natural refrigerants.

The typical store-wide system uses about 3,000-4,000 pounds of HFC refrigerant, usually R404A, which pound-for-pound has a global warming impact that is almost 4,000 times worse than carbon dioxide’s. Supermarkets leak on average about 25% of that refrigerant every year – about 750-1,000 pounds. To put the problem in perspective, that is about 4 million pounds of CO2 -equivalent leaked every year by each supermarket, or 140 billion pounds leaked by the nation’s 35,000 supermarkets. (That is ten zeroes after the number fourteen.) If you want to see how much that is in terms of number of cars on the road, go to the EPA’s greenhouse gas calculator HERE . It’s a nifty little tool that helps us regular people understand the effect of different greenhouse gas emissions relative to each other.

To be clear though, most utilities don’t care one iota about the direct emissions from refrigerant leaks. In fact, many utility regulatory bodies don’t allow their utilities to look at greenhouse gas emissions. All that matters to most utilities across the country is energy use.

Though many utilities advertise their incentive programs under the auspices of energy efficiency and the corresponding environmental benefits, incentives are a pure cost-benefit calculation for utilities. It is cheaper for utilities to pay people and businesses to use less energy than it is to build a new power plant. Period.

So in order to interest utilities in natural refrigerants, you have to come to them with an energy efficiency argument. As discussed in last month’s article, this argument is a no-brainer when it comes to self-contained equipment. The argument for energy savings with natural-refrigerant systems is equally compelling, but it is not a no-brainer.

The amount of energy saved by a store-wide system depends greatly on the type of technology and natural refrigerant used, as well as the average ambient temperature where a store is located. Add to that the fact that every supermarket refrigeration system is individually designed and individually manufactured, and you have the opposite of a no-brainer. Perhaps we should say that it is a “whole brainer.”

The crux of the complexity in determining how much energy a new natural refrigerant supermarket system is going to use lies both in the lack of actual energy data, because the energy consumption has to be estimated before the new store is built, and in the lack of some kind of a baseline against which you’d measure an energy efficiency improvement, because there is no useful national average for the energy usage of a supermarket.

Aaron Daly, Global Energy Coordinator at Whole Foods Market, cited the analogy of the electric car to describe the wholesale shift in approach necessary for natural refrigerants. “We aren’t talking about a car that uses a more efficient gasoline engine; we are talking about a complete shift in the way we do things – an electric vehicle, if you will,” said Daly.

In order for utilities to take advantage of the energy efficiency opportunities that will come from natural refrigerant systems, they’ll need to change the way they do things to a certain extent. Instead of looking at individual components and adding up the energy savings that are achieved by each component, utilities will have to adopt a whole-system approach to energy savings.

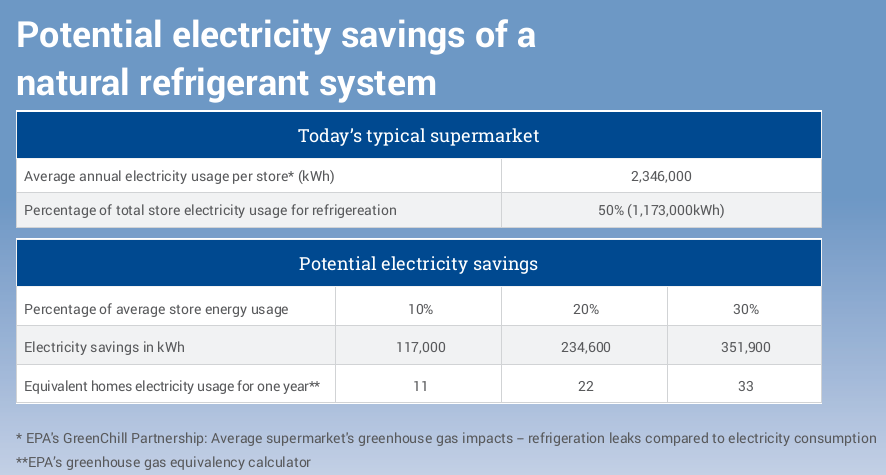

Why should utilities get involved, if this is so complicated? Because the potential savings, ranging from 10% to 30%, are worth it.

In other words, a utility can either try to get 33 homes to stop using electricity completely, or they can help a supermarket install a natural refrigerant system in a new store.

As stated in last month’s article, the main thing that is preventing more supermarket companies from using natural refrigerants in new stores currently is the cost hurdle. Because there are only a few of these natural refrigerant systems in the U.S., equipment manufacturers cannot take advantage of economies of scale.

There just isn’t enough of a market yet for manufacturers to start producing natural refrigerant components here in the U.S. According to Derek Gosselin, Product Manager, Systems Division for Hillphoenix, about 25-30% of the components for a CO2 transcritical system are still imported from overseas.

Tristam Coffin, Energy & Maintenance Project Manager at Whole Foods Market, noted that the lack of trained service techs increases the installation and maintenance costs for natural refrigerant systems. “Many refrigeration contractors remain apprehensive about investing in the training of their techs, because the chances that they’ll have the opportunity to work on a natural refrigerant system are still relatively small.”

For all three of the Whole Foods Market transcritical systems installed in the last two years, Hillphoenix, the system manufacturer, had to take on the responsibility of training the installing/service contractors. In addition, said Coffin, “We received wildly different installation bids from the contractors, because the greater contractor pool simply doesn’t have the experience upon which to base their estimates. Some price low to gain the experience, but the majority pads their pricing, because they are uncertain of what they are getting themselves into.”

Luckily, utility incentives can be quite effective in counteracting the additional costs that often accompany new energy-efficient technologies. This inspires additional sales, which brings costs down, resulting in a virtuous cycle that culminates in the price of natural refrigerant technologies equaling or even beating that of conventional technologies.

GETTING STARTED

So how do we get this party started? Utilities and supermarkets agree on the essential factors in utility programs for natural refrigerant incentives: they have to be easy, transparent, and flexible.

Neither utilities nor supermarkets can afford to take part in a project that takes too much time and too many resources to be worth it. As Paul Anderson, Senior Group Manager of Target Corp. observed “The idea that a utility incentive project would take more time than it takes to actually build a new store is just unworkable for us.”

Ideally, utilities’ methodologies for natural refrigerant incentives would have enough in common across geographies to be somewhat replicable. However this is a challenging notion for individual utilities, which often don’t care about any methodology but their own. But for supermarkets, which may deal with a different utility for every new store, having a methodology that crosses utility borders is essential.

“If we could get utilities to at least agree on a set of principles for how these projects would be handled, it would be enormously beneficial for us,” said Harrison Horning, Director of Energy & Facilities at Delhaize America, which deals with dozens of utilities across the Northeast, the Mid-Atlantic, and the Southeast.

Transparency and flexibility, the other essential characteristics of natural-refrigerant utility incentive programs, might seem to be in opposition to each other, but both are essential for a successful program for supermarkets.

Mitch Knapke, Director of Food Retail at Emerson Climate Technologies, perhaps stated it best when he said, “Many people mistakenly believe that transparency means a lack of flexibility. I disagree. A transparent system can be highly flexible, as it would need to be in the case of utility incentives for natural refrigerant use in supermarket systems.”

As stressed in the Berkeley workshop, a flexible and transparent model is needed to predict the energy consumption of a new store at the design phase, as well as a baseline against which the energy efficiency improvements would be compared.

With a multitude of models available on the market, the hard part isn’t coming up with one. It is to get utilities and supermarkets to agree on which model to use. Every model has its flaws; but for utility incentive projects for new stores that will use natural refrigerants, there is no alternative but to rely on modeling when predicting the energy usage of a store that is yet to be built.

Most at the workshop agreed that the question of a baseline is the more complicated question. Once you have modeled the energy usage of a natural refrigerant system in a new store, what do you measure it against?

The choices are numerous. Do you measure the new store’s energy consumption against a national average for all stores? The only thing that is certain about a national average is that it will likely be irrelevant for any one particular store. What about a regional average? That would be more relevant for a particular store in terms of the ambient air temperature in a region, but it probably won’t correspond to the size or the cooling capacity of a particular store, and it might not have anything to do with the standard refrigeration technology used by a particular company. It wouldn’t make sense to use a centralized DX system as a baseline for a company that hasn’t built that type of system for over a decade.

A FLEXIBLE APPROACH

The consensus at the workshop seemed to be that an ideal baseline is whatever the company would have built in that spot instead of the natural refrigerant system. So for a company like Target, for instance, which said last year that its standard system for new stores will be a CO2 cascade system, you’d use a CO2 cascade system as the baseline.

Of course, the chances aren’t high that Target has a store already in operation right down the block that can be used as the baseline. So even in a situation where a company has declared a standard technology, the baseline question still isn’t easy to answer.

You could take actual numbers from a store that is close to the new site, and try to determine the extent to which energy usage would differ at the new store. You could take an average of the energy usage data from the company’s existing stores in the region. You could also ask the company that is applying for the incentive to draw up a store plan for the technology that would have been used, if not for the natural refrigerant choice, and then model the energy consumption of that store. Many would see this as a useless exercise, but it might actually save a lot of time vs. some of the other baseline possibilities.

How to we get utilities to agree on one of these baseline methodologies? We don’t. The purpose of the workshop was not to get everyone to agree on one universally acceptable methodology for every project. The purpose was to come up with a set of transparent methodologies affording the flexibility to pick the best for each individual project.

Perhaps with additional discussion, utilities and supermarkets can come up with a hierarchy of baseline methodologies. If a company has a standard methodology, with actual energy usage data from another nearby store that is relevant, use that as the baseline. If a company has a standard methodology, but does not have actual energy consumption data from an existing store close to the new store’s location, use a regional average of several of the company’s stores that are within a certain radius of the new store. If a company does not have a standard technology that would have been installed in the store under consideration, take the alternative store design that wasn’t chosen, under the assumption that it would have been used but for the natural refrigerant technology chosen instead. And so on.

That might sound complicated and time consuming, but according to all participants in the workshop, it cannot possibly be as time consuming and complicated as starting anew, from scratch, for every new store, in every region, with each different utility. Nothing is worse than that.